Session 1

Introduction to Systems Health

This session will delve into the key components of the healthcare system, emphasizing the concepts of interdependence and complexity, particularly in relation to health financing. Through practical examples, we will learn how these interdependent elements shape the everyday realities and challenges within the healthcare system.

Activity 1.1.1: Defining Complex Adaptive Systems

In your groups develop a definition of complex adaptive systems for health systems focusing on the building blocks, any additional dimensions as well as complexity and interconnectedness.

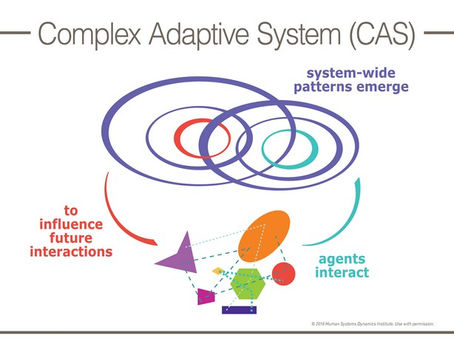

A Complex Adaptive System (CAS) refers to a system that is characterised by having a substantial number of agents that have correlated interactions with one another. CASs display self-organisation, in that control tends to be highly dispersed and decentralised. Self-organisation and nonlinear behaviour create emergent, global properties for the whole system. The overall coherent behaviour of the system is the result of a huge number of decisions made every moment by many individual agents. An example of a CAS is forests, organisations, stock markets and communities. We cannot predict the behaviour of a whole CAS from the basis of its constituent agents (due to nonlinearity), as it is possible for a small change in one variable to shift the entire system into a very different state (such as consumers in a market). A CAS has a memory and time base. It is a path dependent system that is anchored by its initial conditions, so that identical forces acted onto seemingly similar systems might react differently depending on their history. CAS have a degree of resilience to external forces depending on factors such as the diversity of its agents, the quality of network links and its proximity to any critical thresholds.

Focusing on the health financing building block in the context of CAS, our group has focused on the recent signing of the NHI as an artefact. We noted how the top-down approach of the policy affected(negatively) other stakeholders in the healthcare system and resultantly led to resistance from the lower-level stakeholders as the one decision had financial implications with regards to resource allocation for the entire healthcare system. This is a demonstration of path-dependence.

Further Learning: Complex Systems

Self-Organisation in Complex Systems

Complex systems, such as those seen in healthcare, operate through intricate networks of interactions among their components. Complexity theory examines how these systems evolve, adapt, and sustain themselves without reliance on centralised control (Thille et al., 2024). At its core, this perspective assumes that the activities and outcomes within a system, whether a primary care clinic or a broader healthcare network, result from dynamic relationships between agents. These agents include human participants, like clinicians and patients, and non-human elements, such as electronic medical records (EMRs), clinic spaces, or even regulatory frameworks (Thille et al., 2024).

These relationships are not static. Agents act and react to each other’s behaviours, creating a process of co-evolution or co-emergence (Burman & Aphane, 2016). The result is a system that changes in unpredictable ways, where stability is only ever temporary and emergent. This concept of change challenges traditional models that seek linear, predictable cause-and-effect pathways. Instead, complex systems adapt through self-organisation, where patterns of order emerge organically from interactions between interdependent agents rather than from an overarching plan or authority (Pincus & Metten, 2010).

Self-Organisation Defined

While self-organisation doesn't have a single accepted definition, it is widely understood as the process by which systems regulate and reorder themselves through interactions among their elements (Pincus & Metten, 2010). These interactions create localised behaviours and adaptations, leading to emergent global patterns. Importantly, self-organising systems are characterised by their autonomy; they do not rely on external direction to maintain their coherence (Thille et al., 2024).

In the context of healthcare, self-organisation occurs as clinicians, administrative staff, technologies, and other elements of the system respond to internal and external pressures (Thille et al., 2024). For example, a primary care clinic faced with the introduction of a new health professional must reorganise its workflows to integrate the new role effectively (Thille et al., 2024). This adaptation is not dictated by a central authority but emerges from the interactions and adjustments made by the clinic’s agents as they navigate their interdependencies.

Dynamics of Interaction and Feedback

Self-organisation in complex systems is driven by dynamic feedback loops. These feedback loops operate both horizontally (among agents within the same layer of the system) and vertically (between local actions and broader organisational structures) (Pincus & Metten, 2010). For example, when clinicians collaborate to align their workflows with new technologies, they generate localised patterns of practice. These patterns, in turn, influence organisational norms, which then feedback to shape individual behaviours (Thille et al., 2024).

The interaction of horizontal and vertical feedback creates a system that is self-sustaining over time, capable of both stability and evolution (Pincus & Metten, 2010). However, these dynamics also mean that outcomes are highly unpredictable. Change within the system is non-linear; a small adjustment at the local level can ripple through the system, producing disproportionately large or entirely unexpected effects (Pincus & Metten, 2010).

Healthcare as a Self-Organising System

Healthcare systems, particularly in primary care settings, epitomise the principles of complexity and self-organisation (Thille et al., 2024). Primary care practices are subject to a confluence of internal and external pressures, each of which demands constant adaptation. Internally, clinics must manage diverse roles, workflows, and resources. Externally, they respond to health policies, funding models, and community health needs (Thille et al., 2024).

For example, many Canadian provinces have introduced interprofessional teams to primary care, integrating new professions such as nurse practitioners or social workers (Thille et al., 2024). Each new role introduces an internal change agent, requiring adjustments in workflows, communication, and inter-professional relationships. This process of integration is not linear or predictable; instead, it depends on the local context of the clinic and the unique interactions between its agents.

External agents - such as government organisations, disease-focused non-profits, and private corporations - seek to influence primary care systems with their own agendas (Thille et al., 2024). These agents may introduce new guidelines, technologies, or funding incentives, each of which creates further change pressures. The overlapping and sometimes conflicting priorities of these agents can result in unintended consequences. For instance, a clinic may adopt a new electronic medical record system to comply with funding requirements, only to face disruptions in communication and workflow that require further adaptation (Thille et al., 2024).

Adding to these complexities are extreme events, such as pandemics, which force rapid reorganisation of services. During a crisis, primary care systems must align with new policies, accommodate shifting resource availability, and respond to evolving community health needs. These changes often occur under conditions of uncertainty, making self-organisation both a necessity and a challenge (Burman & Aphane, 2016).

Emergence and Adaptation

The most clear indication of self-organisation is the emergence of new patterns and behaviours (Pincus & Metten, 2010). In healthcare, this emergence can be seen in the development of innovative care models, new workflows, or unexpected collaborations. These emergent phenomena are not reducible to the actions of individual agents but arise from the system’s collective dynamics (Pincus & Metten, 2010).

For example, a clinic adapting to the pressures of a pandemic may develop entirely new methods for telehealth delivery (Pincus & Metten, 2010). These methods may not have been planned in advance but emerge as clinicians, administrators, and patients interact and adapt to the constraints of remote care. Over time, these local innovations can influence broader healthcare practices, creating a feedback loop that drives further change.

However, the emergent nature of self-organisation also means that change efforts are inherently uncertain (Pincus & Metten, 2010). Not all attempts at adaptation succeed, and failures can have cascading effects throughout the system. In extreme cases, systems may experience collapse if they are unable to cope with the demands placed upon them.

Implications for Managing Complexity in Healthcare

Understanding self-organisation offers valuable insights into the management of healthcare systems. Traditional, top-down approaches that rely on centralised control are often ill-suited to the dynamic and interdependent nature of complex systems (Burman & Aphane, 2016). Instead, effective management must focus on enabling local adaptability and fostering the conditions for self-organisation (Burman & Aphane, 2016).

This perspective has significant implications for research and practice. For example, proponents of complexity theory argue for the use of non-experimental and mixed-methods approaches to study the dynamic relationships within healthcare systems (Thille et al., 2024). These methods can capture the nuances of real-time adaptation and provide a more comprehensive understanding of how change occurs.

At the same time, acknowledging the unpredictability of self-organisation challenges the expectation of stable, long-term solutions (Tao & Liu, 2015). In healthcare, any new intervention or policy must be understood as a temporary accomplishment, subject to ongoing feedback and adjustment. This mindset shifts the focus from rigid implementation to continuous learning and evolution.

Conclusion

Self-organisation is a fundamental process that underpins the dynamics of complex systems, including healthcare. By examining how agents within a system interact and adapt, we gain a deeper understanding of how order and change emerge organically. In the context of primary care, this perspective highlights the importance of local adaptability, the role of feedback loops, and the inevitability of non-linear and unpredictable change. Embracing the principles of complexity and self-organisation offers a pathway to more resilient and responsive healthcare systems, capable of navigating the challenges of a constantly evolving landscape.

References:

Burman, C. J., & Aphane, M. (2016). Community viral load management: can ‘attractors’ contribute to developing an improved bio-social response to HIV risk-reduction? Nonlinear Dynamics Psychol Life Sci, 20(1), 81-116.

Pincus, D., & Metten, A. (2010). Nonlinear dynamics in biopsychosocial resilience. Nonlinear dynamics, psychology, and life sciences, 14(4), 353.

Tao, L., & Liu, J. (2015). Understanding self-organized regularities in healthcare services based on autonomy oriented modeling. Nat Comput, 14(1), 7-24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11047-014-9472-3

Thille, P., Tobin, A., Evans, J. M., Katz, A., & Russell, G. M. (2024). Evolving through multiple, co-existing pressures to change: a case study of self-organization in primary care during the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada. BMC Primary Care, 25(1), 285. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-024-02520-3